Lesley S. Pullen discusses the relationship between textile art and sculpture in the classical Javanese era.

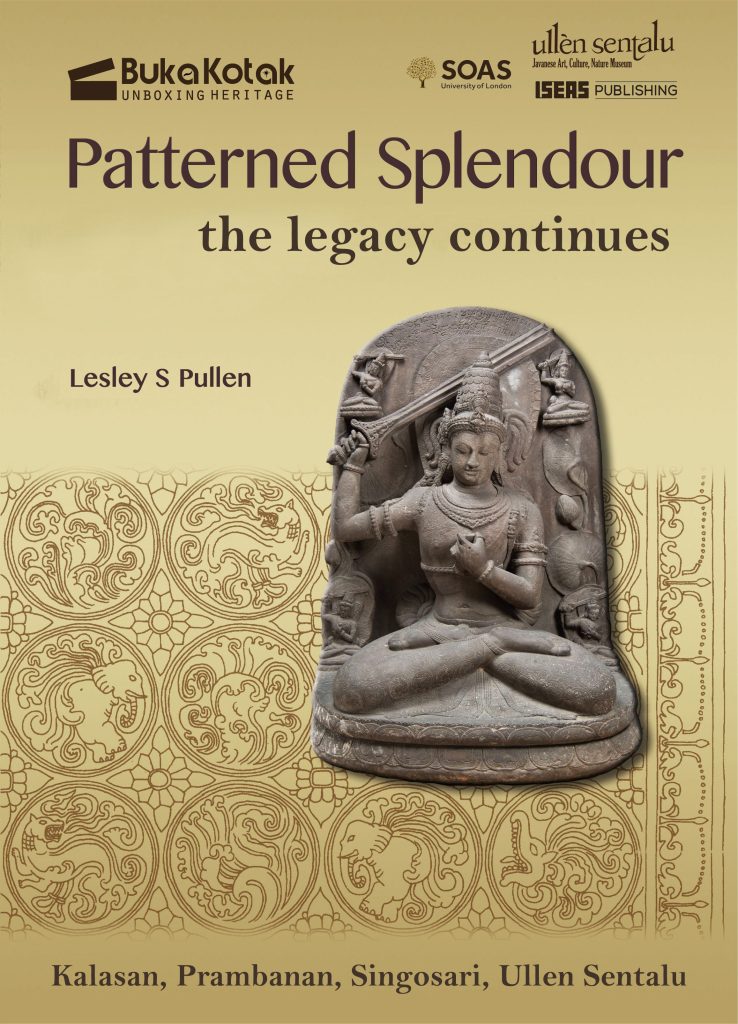

Art historian Lesley S. Pullen explores how classical Javanese sculptures intricately depict textile patterns, revealing the island’s role in ancient trade and the symbolic power of fabric in religious and royal art. A Patterned Splendour documentary highlights Kalasan, Prambanan, and Singosari temples—where these motifs originated—and showcases their legacy through Ullen Sentalu Museum’s textile collection.

Lesley S. Pullen is an art historian specializing in the material culture of South and Southeast Asia during the medieval period. She earned her doctorate from SOAS, University of London in 2017, with research focused on the representation of textiles in classical Javanese sculpture. Lesley has written extensively on Javanese art and has been teaching Southeast Asian Art at SOAS and the Victoria & Albert Museum since 2015.

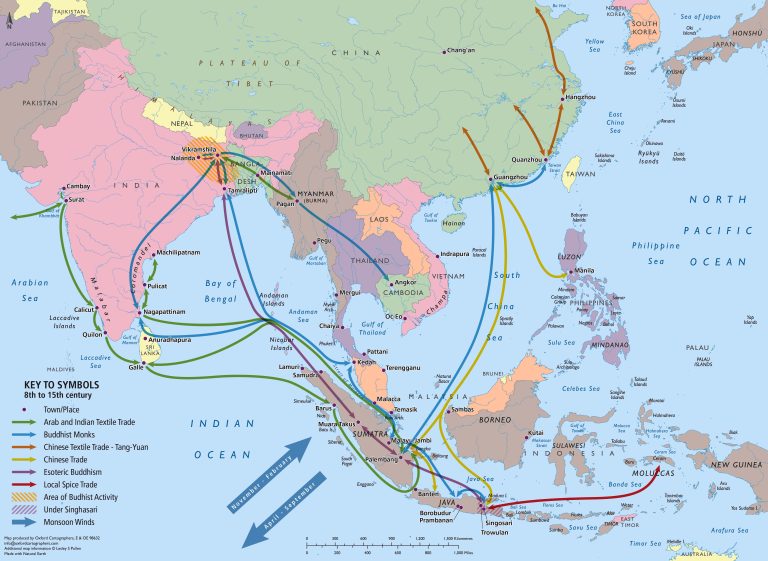

Mataram reached its peak between the 8th and 10th centuries by constructing grand temples such as Prambanan and Borobudur. A close cultural relationship also formed between Java and Champa, reflecting the interconnected dynamics of the Austronesian world.

Kalasan Temple honors the Goddess Tara with magnificent reliefs. The Dwarapala statues discovered there display a blend of Indian and Javanese styles through carved textiles and spiritual guardian symbols.

Prambanan is not only architecturally grand but also spiritually meaningful. The iconography of Shiva and inscriptions from Ratu Baka illustrate the acceptance of Tantric teachings in 9th-century Java.

Ullen Sentalu weaves together art, batik, and Javanese history in one space. Its symbolic location and collections—ranging from Vorstenlanden Batik to Peranakan Batik—make it a vibrant site of cultural preservation.

The Singhasari period brought sculpture to new heights of detail, influenced by cosmopolitan elements from China, Central Asia, and local esoteric beliefs under King Kertanegara. The statue of Goddess Parwati features textile patterns spanning continents, reflecting Java's role in the global textile trade. Despite three damaged statues in Singhasari, the remnants of the kawung motif still signify high status and the symbolic power preserved in Javanese royal art.

In the Majapahit era, sinjang cloth with kawung motifs became an exclusive symbol of kings and queens. Textiles were more than garments—they were emblems of power reserved only for the royal bloodline.

Mataram Empire, sometimes called Mataram Kingdom, was an Indianized kingdom based in Central Java around modern-day Yogyakarta between the 8th and 10th centuries. The kingdom was ruled by the Sailendra dynasty and later by the Sanjaya dynasty. The monumental Hindu temple of Prambanan near Yogyakarta was built in the 10th century.

In 750 CE—850 CE, the kingdom saw classical Javanese art and architecture blossom. A rapid increase in temple construction occurred across the landscape of its heartland in Mataram (Kedu Plain). The most notable temples constructed in Mataram are Kalasan, Sewu, Borobudur, and Prambanan. The Empire had become the supreme power in Java and over the Srivijaya Empire, Bali, southern Thailand, some Philippine kingdoms, and Khmer in Cambodia.

The Javanese kingdoms maintained a close relationship with the Champa polities of mainland Southeast Asia as early as the Sanjaya dynasty. Like the Javanese, the Chams are an Austronesian people. An example of their relationship can be seen in the architecture of Cham temples, which share several similarities with temples in central Java built during the Sanjaya dynasty.

The Buddhist sanctuary has a square plan with one large and three small chambers. The large chamber contains an altar that once supported the main image. It is believed to have been a large bronze statue of the female deity Tara. On the outside of the temple, around each doorway, are vertical friezes of foliate lotus leaves scrolling vertically up and down the building. The niches around Kalasan temple, are adorned with carvings of Kala heads and scenes of deities: devatas and apsaras in scenes of Hindu-Buddhist heaven.

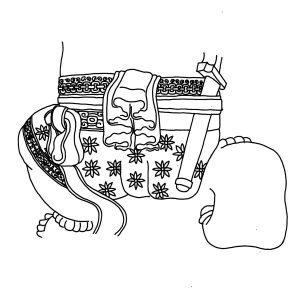

This stone dvarapāla, or guardian figure, dates to the 11th century and remains in the garden of Museum Sonobudoyo. Its textile pattern is closely related to those from Central Java. The patterned kain represents a simple four-petal flower edged with a brocaded border. The dress style accurately replicates the equivalent of an Indian dhotī, where the cloth is pulled between the legs, tucked behind, held by a metal belt, and overlaid with a fabric sash. The detailed carving of the border pattern on the textile and the chains on the belt attest to the sophistication of the craftsman. The figure has sizeable round earplugs, bulging eyes and flaring hair; all these aspects attest to his character as a guardian figure.

The Prambanan temple complex is one of Southeast Asia’s most significant Hindu temples, rivalling Borobudur (the world’s largest Buddhist temple). Built in the 10th century, this is the largest temple compound dedicated to Shiva in Indonesia. Rising above the centre of the last of these concentric squares are three temples decorated with reliefs illustrating the epic of the Ramayana, dedicated to the three great Hindu divinities (Shiva, Vishnu and Brahma).

The academic symbolism of the Prambanan temple complex is revealed in its iconography, dominated by the image of the four-armed Shiva, the Great Teacher—the customary Indonesian representation of the supreme deity. Prambanan affirms the Shaivite path to salvation; the path is indicated in the inscription of 856, which implies that the king had practised asceticism, the form of worship most acceptable to Shiva. Thus, Shaivism and Mahayana Buddhism had become hospitable to Tantric influences in Java.

An almost contemporary inscription from the Ratu Baka plateau, which is not far from the Prambanan complex, provides further evidence of Tantrism; it alludes to special rites for awakening Shiva’s divine energy through the medium of a ritual consort.

Ullen Sentalu, Javanese Art, Culture and Nature Museum is located at the foothill of Mount Merapi. The northern part of macro-cosmology line of Recent Mataram Kingdom that ended up in the South Sea in the southern part of Yogyakarta Special District. It has an exquisite collection of Batik Vorstenlanden that originated from the Royal Courts of the Kraton and the Puro in Yogyakarta and Surakarta.

The Museum is also located in the centre of Old Mataram Kingdom where Prambanan temples complex of Sanjaya Kingdom located in the East and Borobudur temple of Syailendra Kingdom in the West.

The stone carving tradition of relief and sculpture from Old Mataram still alive today with the impressive reliefs and sculptures in Ullen Sentalu Museum.

The museum also features the Esther Huis room, which preserves the masterpiece patterns of Peranakan Batik from the Indies culture.

Indonesia’s history has been profoundly influenced by its geography, trade, religion, and artistic expression. Java played a central role in international trade during the Medang and Singhasāri periods, attracting ships from India and China, as documented in Javanese and Chinese records. The Javanese people were renowned for their religious sculptures in bronze, gold, silver, and stone, which held deep spiritual meaning and demonstrated advanced craftsmanship. Java’s religious landscape reflected a syncretic blend of Hinduism and Buddhism, evident in the styles of its sculptures. Pilgrimages to India and cultural exchanges influenced local art, while Javanese metalwork and textiles may have, in turn, inspired Tibetan designs. Java and Sumatra also developed a sophisticated textile culture, often reflected in the detailed carvings of their statues.

Documentation in the form of inscriptions and monuments ceased in central Java after the beginning of the 10th century. Evidence of these years’ events comes almost exclusively from the Brantas River valley and the adjacent valleys of eastern Java. This abrupt shift in the locus of documentation has never been satisfactorily explained.

Changed economic circumstances in the archipelago had an essential impact on Java beginning in the 13th century; however, long before the 12th century, Chinese shipping had become capable of distant voyages, and Chinese merchants sailed directly to the numerous producing centres in the archipelago. The eastern Javanese ports became more prosperous than ever before.

During the East Java period, three clear dynastic periods were identified. And three styles of sculpture. The Kadiri, Singasari and Majapahit periods. During the earliest and longest of these, the Kadiri. There were only a few statues carved before 1222. They were small and relatively unsophisticated and appeared to have no evidence of textile patterns. During the Singhasāri period from 1222 to 1292, many sculptures were carved in stone. At this time, no bronze statues were made. Especially during the reign of King Kṛtanāgara, here was the height of artistic achievement for Javanese sculpture. He thought of himself as a Shiva and Buddha in his lifetime and after his death and was a follower of esoteric practices.

Indeed, such religious and political authority enabled Krtanāgara to take advantage of circumstances stemming from Chinese trade in the archipelago to extend his divine power beyond Java. By the 14th century, the homage of overseas rulers to the Javanese king was taken for granted.

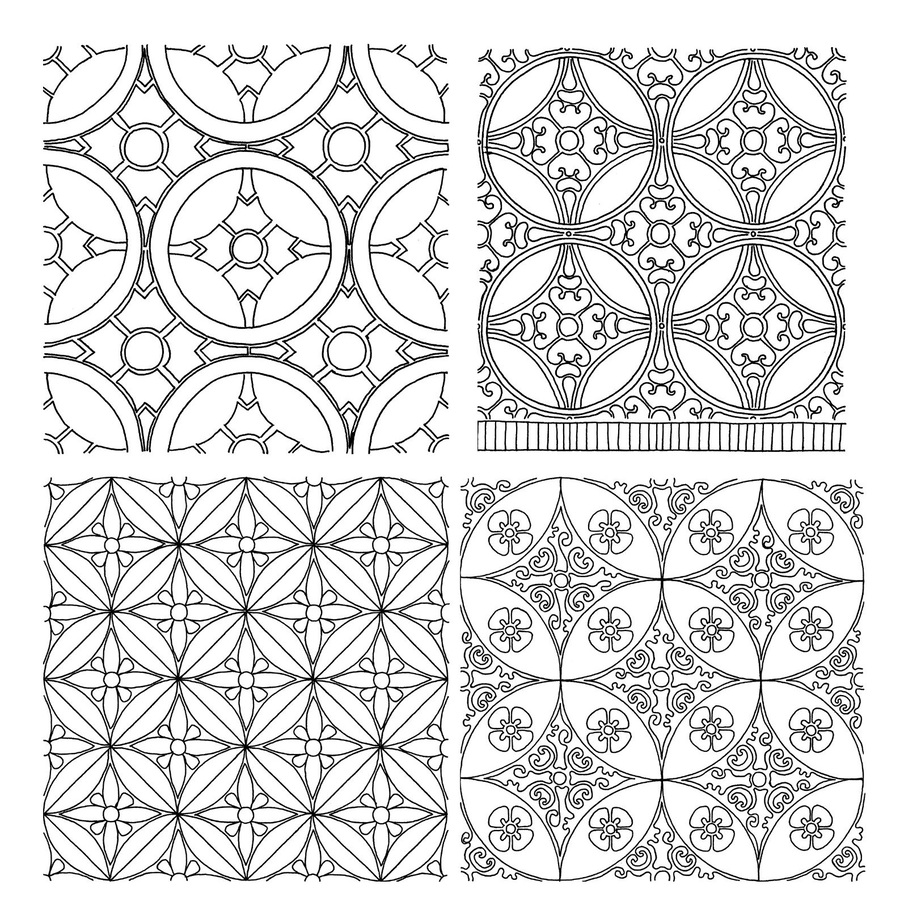

The number of statues carved was extensive. Many of the statues were carved with intricate and detailed textile patterns. Many patterns on the sculptures reflect textiles that would have been traded in from China or the Sassanian world in Central Asia, along with some from West Asia. Carved statues, especially during the Singhasāri period, are complex and detailed in their designs. They all wear lower-body garments, an upper-body jacket, and a sash across the torso. All statues are depicted with a different and detailed textile pattern. Many reflect an Indigenous design, probably a textile made in Java, but some reflect textiles that would have been traded, perhaps from the Chinese world.

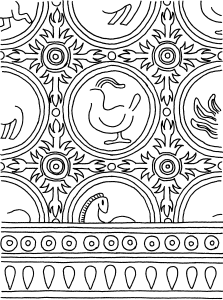

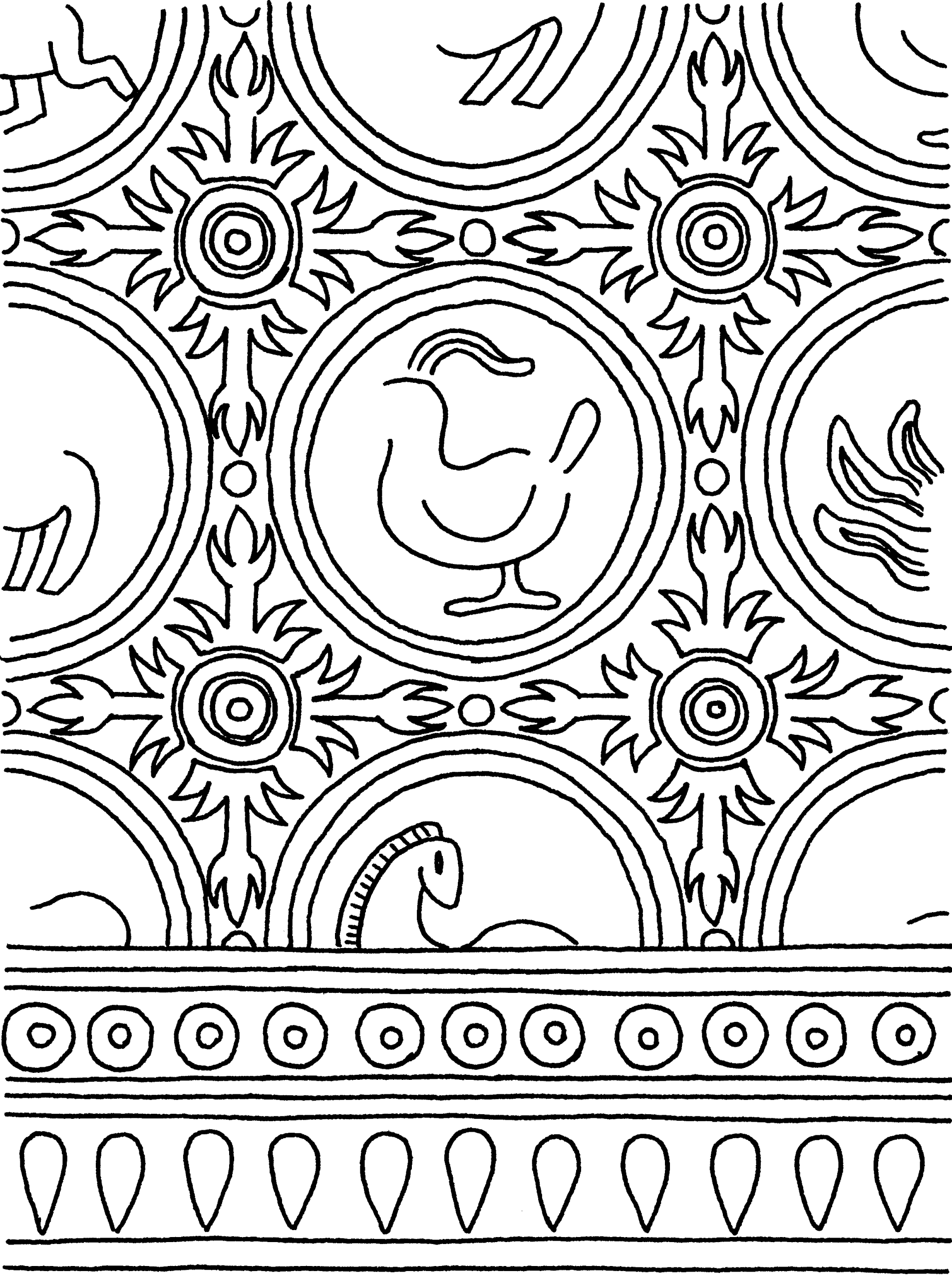

This important statue of the Buddhist goddess Parvati Retinue remains in situ at the Candi Singosari. Two attendants accompany her on either side. The statue is considerably damaged, her head Is not original, and part of the base is broken away. Her hands are together in an̄jalimudra at the front of her body. The lower body garment is carved in a detailed but faded textile pattern. The pattern comprises concentric or touching circles, which feature animals with four legs and ducks. This pattern indicates designs we see in Central Asia, also from western India and Burma and China. Therefore, we see the designs on this Parvati as reflecting once again the position that Java held in international trade.

Following a careful and extensive study of textiles and paintings from India, Central Asia, Burma, and China, it can be suggested that several examples closely fit the pattern of this statue. These examples undoubtedly indicate that the sculptor of this unique pattern did not use a Javanese textile but rather those from Central Asia or China. The definition of a duck within a pattern, either woven in silk or block printed on cotton, appears on many different textiles and wall artwork. Textiles have, for millennia, been part of a tradition of gift-giving and tribute and have been carried by traders to foreign lands.

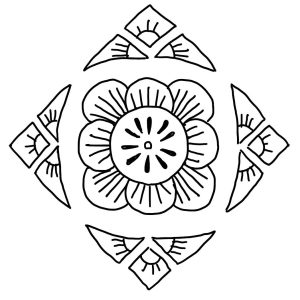

On the grounds of Candi Singosari are three small statues, both significantly damaged. One is Prajñāpāramitā, an Unknown goddess and one of a Dikpala, a guardian of the directions). All three were decorated with textile patterns, now almost wholly lost to the harsh climate of Java. These statues were all adorned with elaborate jewels and detailed textile patterns. The patterns appear as variations of the kawung motif, attest to the longevity of this much-revered pattern in Java, and highlight that royal figures were adorned with this particular pattern.

After King Kṛtanāgara died in 1222, the capital was moved to Majapahit. For some years, the new ruler and his son, who regarded themselves as successors of Krtanāgara, had to suppress rebellions in Java; not until 1319 was Majapahit authority firmly established in Java with the assistance of the renowned soldier Gajah Mada. Gajah Mada was the chief officer of state during the reign of Kṛtanāgara’s daughter Tribhuvana (c. 1328–50), and in these years, Javanese influence was restored in Bali, Sumatra, and Borneo. Kṛtanāgara’s great-grandson, Hayam Wuruk, became king in 1350 under the name Rājasanagara.

Peace reigned during the Majapahit period in Java, and the island became very wealthy. The people from the eastern islands of the archipelago brought their spices to trade in Java for rice. These spices were subsequently traded again for textiles from India and China.

Many prominent and small temples were built. The main temple at Candi Panataran is guarded at the entrance of each flight of steps by two large guardian statues. A small female attendant accompanies this dvarapāla. The pattern of the textiles represents the interlocking circles of the kawung design in a very detailed form. Around the hips are girdles and ornaments, probably in gold, hanging down to the front of the legs. The Dvarapāla is holding on to a large club. Below the knees overlaying the hips is a wide sash. All these textiles are carved in the pattern of the kawung. This design became synonymous with this period in East Java and was worn by many statues deified as kings and Queens, images of gods and goddesses. Almost all the Majapahit large statues of kings and queens are carved with the sinjang in the kawung pattern, which had deeply symbolic meanings for the kings and Queens of the Majapahit period. It could have been made with imported gold leaf or woven with a gold thread and appeared to hold profoundly symbolic meaning for the monarchs, as only a few statues were carved with variations of this same pattern. Minor nobility of smaller statues was prohibited from using this prodigious kawung-patterned sinjang in their sculptures.

This is fascinating! Thank you!